Although the recent UN Bonn Climate Change Conference was to be held at a technical level, the negotiating parties were unable to circumvent the major political issues of emissions reduction, financing, and loss and damage. Thus, although serious discussions have taken place, the incoming Czech EU Council Presidency will have ample tasks on its hands, because negotiations need to shift to a higher pace during the autumn in order to respond to the urgency required by climate change. An on-site analysis of the outcomes of the conference by the Green Policy Center.

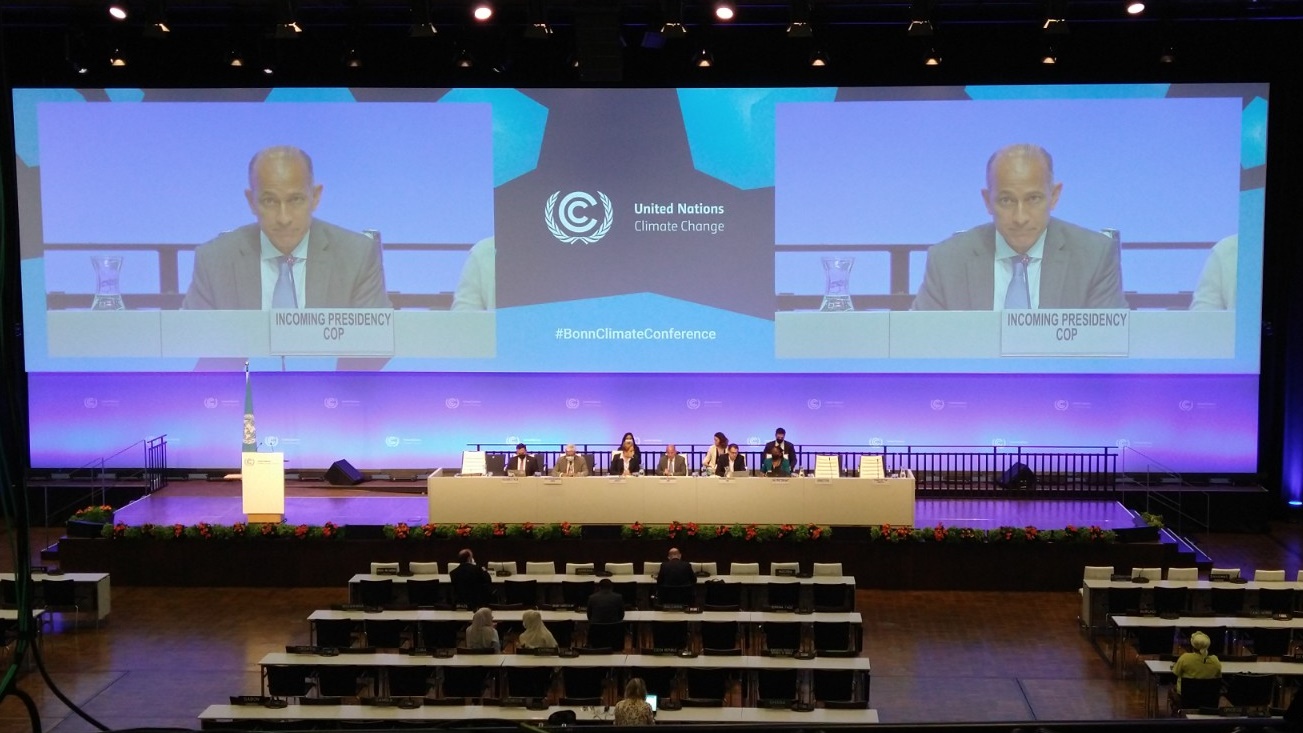

Technical level meetings took place during the second and third weeks of June in Bonn, Germany under the Subsidiary Bodies of the UNFCCC, the UN body dedicated to climate change. This two-week conference was significant in several ways; as it was the first time these technical discussions were held in person since the two-year Covid induced break, and the Framework Convention on Climate Change was signed in June 30 years ago. On the one hand, this demonstrates the international community’s commitment to multilateralism, but it also shows that the pace of negotiations has not yet been able to keep up with the urgency of tackling climate change. During the conference, the Green Policy Center supported the work of the Czech Republic, which will take over the rotating EU presidency on 1 July, thus gaining insight into the negotiations. We present the main results of the conference, as well as the tasks ahead below.

Although there were already some surprises and diplomatic scandals during the preparatory talks and the opening sessions, the negotiations took place in a professional and technical manner during the two-week series of talks including delegates from more than 100 countries. During the opening session, representatives of the Russian Federation tried to rationalise the aggression against Ukraine, to which a significant part of the participants walked out of the plenary. Although Ukraine and Russia also tried to thematize the war – on one occasion for example, representatives of Ukraine, called for the autumn workshops not to be held in person but online because they did not have usable airports at the moment due to the war – these did not affect the international climate policy talks. The most controversial topics were rather the ambition levels of emission reduction, financing loss and damage, and financing climate action.

At the previous climate summit held in 2021 in Glasgow, countries agreed to develop a new emission reduction work program to increase ambition by 2030 in order to meet the 1.5 ° C temperature target set in the Paris Agreement. The details of this work program have now been addressed for the first time, leading to very serious discussions. Due to the fact that this work program applies to both developed and developing countries, developing countries have sought to slow down negotiations and squeeze concessions from developed countries in the areas of adaptation, financing and technology transfer. In addition, developed countries, led by the EU and its Member States, have navigated themselves into a smaller trap, as they have always tried to push countries to a higher level of ambition by referring to the latest scientific findings, but now this card has been played mostly by developing countries. In its recent report, the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) addressed the topic of a global ‘carbon budget’ in detail.

The concept of a global ‘carbon budget’ refers to how much greenhouse gas humanity can potentially release into the atmosphere while still maintaining the 1.5°C temperature goal. According to developing countries, since developed countries have been emitting carbon dioxide into the atmosphere since the 1800s, developing countries should receive a proportionately larger slice of this remaining carbon budget. The EU and other developed countries, of course, will not be able to dispute the scientific findings of the IPCC in their statements, since they were basin their arguments on other similar reports previously, so it will be difficult for them to sweep the subject off the table during upcoming negotiations.

The situation is similar regarding national climate commitments, as they are currently insufficient to reach the 1.5°C target, so it would be important for all countries to make more ambitious commitments ahead of the UN climate summit in November to be held in Egypt. However, according to the historical responsibility referred above, developing countries expect this increase in ambition to come from developed countries mainly. Thus, the EU is also in a difficult position here, having recently increased its 2030 commitment from an at least 40% emission reduction to 55% target – and the details of the package are still being negotiated – so it is questionable whether the EU and its Member States will come to the November climate summit empty-handed.

The perception of the EU and developed countries on some other issues is also problematic, as mentioned, there has been a debate between developed and developing countries in the run-up to the conference on the inclusion of Loss and Damage on the agenda. The latter wanting to include the topic of Loss and Damage, which aims to finance the costs of the negative effects of climate change, such as natural catastrophes. Developed countries, on the other hand, feared that this could lead to all sorts lawsuits to pay for these damages. They would rather finance these costs through the work of existing international green financial organizations such as the Adaptation Fund or the Green Climate Fund. At the end of the talks, however, the will of the developing countries prevailed, as the issue is likely to be addressed by the countries at the Egyptian climate summit in November.

When it comes to finances, we can also expect difficult negotiations in the coming months, as the $100 billion annual climate finance target set for 2020-2025 is to be revised and a new target should be agreed. Developing countries are expecting to agree on an even larger sum, and linking the implementation of their emission reduction commitments to the existence of available financial resources and technology transfer, not to mention raising their level of emission reduction ambition.

In contrast to the above difficulties, the negotiations on the modalities of the international emission reduction projects under article 6 were almost refreshing, the co-facilitators of the current session found the negotiations literally boring compared to the previous debates, i.e. the negotiations went smoothly. Although further work on a number of issues is expected in the autumn, it looks like it will be possible to reach an agreement on the subject in November, and international emission reduction projects could start soon.

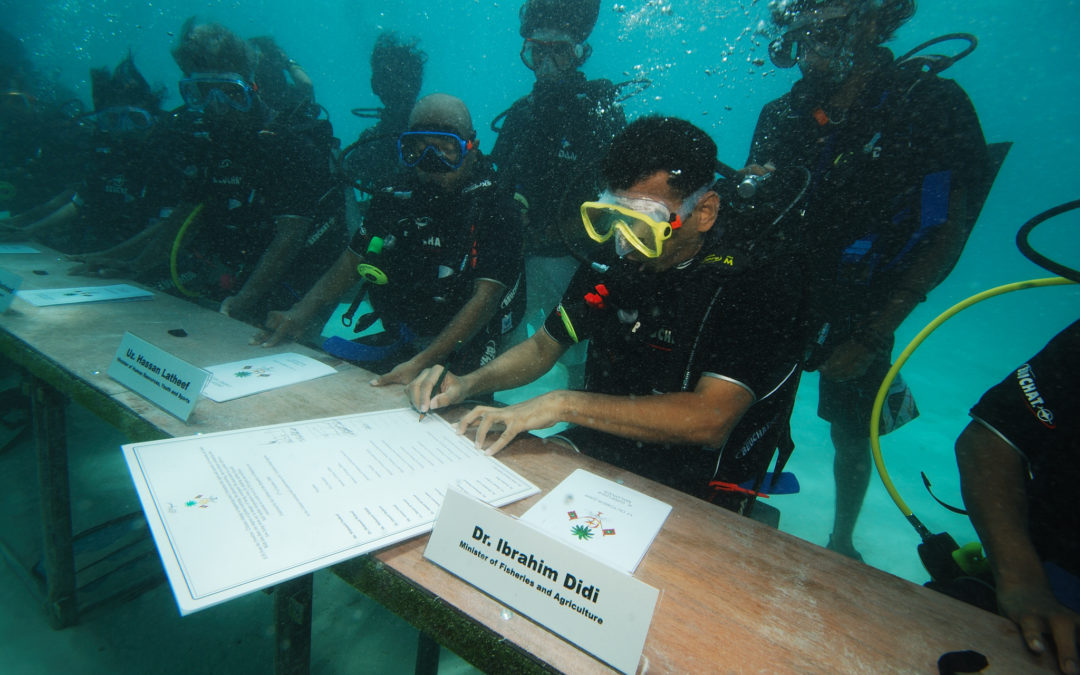

Given that the November conference will be held in Egypt, there is a great deal of pressure on the incoming Egyptian presidency both from African countries to make serious progress on finance, adaptation and agriculture, while developed countries and small island states expect significant progress in reducing emissions.

Overall, the June session showed the topics on which the incoming Egyptian Presidency needs to bring the various interests closer. Meanwhile also pointed out that the EU and its Member States need to review and update several of their previous positions for example on loss and damage and financing, and that we have to find new allies in order to make the November climate summit a success. Experts from the Green Policy Center will continue to support the Czech Republic, which will take over the rotating EU Council Presidency on 1 July, in addressing the above-mentioned international challenges within the framework of the UN.