As some time has passed since the COP27 UN climate conference has ended and the process celebrated its 30th anniversary, it is worth taking a look at the future of the climate negotiations.

Negotiations under the 27th Conference of Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change ended on a Sunday morning at 9:20 a.m. almost setting a new record as part of the 30-year process. With the negotiations running almost two days past the planned closing date, we had the second longest climate conference, where unfortunately some negative records were broken as well; this event was attended by the largest number of oil and gas industry lobbyists to date, more than 600 people, which represents a 25% increase compared to the previous year. Voices suggesting the reform of the process could already be heard before, but after the setbacks of the last COP, they became even stronger. After a quick overview of the results of the conference, we will attempt to outline a possible future of the process.

This year’s climate conference was preceded by high expectations, mostly from the developing world, since the COP26 held in Glasgow mostly dealt with emission reduction, so they saw the role of this year’s conference in financial matters, adaptation and the implementation of commitments. These expectations were only partially fulfilled, because while it is truly historically significant that a financial fund was set up to compensate for the damage caused by the negative effects of climate change, but at the same time, it was not possible to increase the ambition considered necessary by science to prevent these damages, i.e. to reduce emissions level. At the conference, the will of some vocal minority developing countries prevailed – with the effective participation of the Egyptian COP presidency – as the complete phase out of fossil energy sources, the peaking of emissions by 2025 or higher emission reduction targets were not included in the closing document of the conference. Not only the European Union and most developed countries, but also the small island countries most threatened by climate change cannot be satisfied with this.

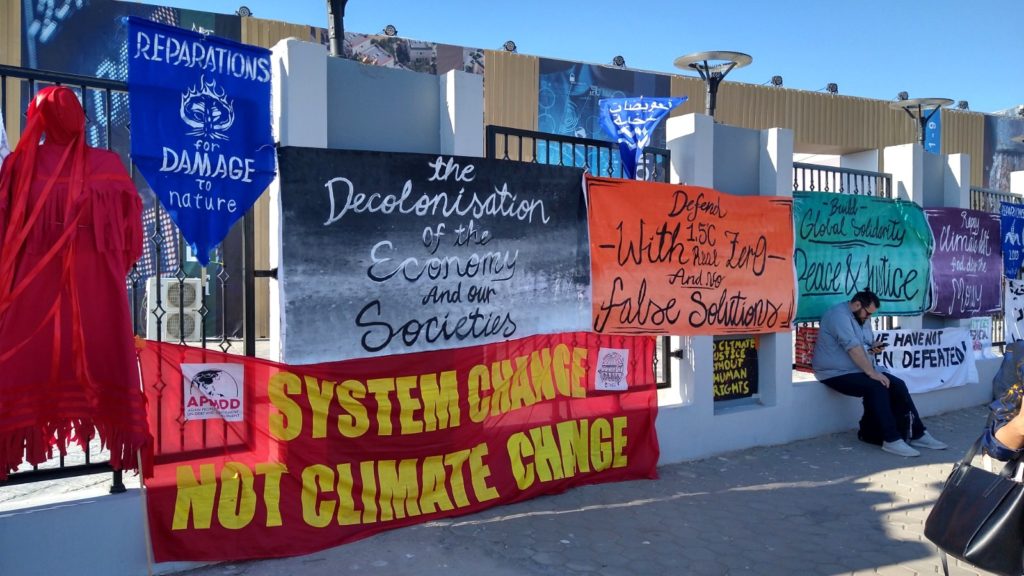

The moderate overall results of the COP27 climate conference, the challenges surrounding the organization, such as the multiple overpricing of hotels, office leases, food and drinks; the lack of drinking water, or the incomplete building of the conference venue and the lack of transparency on the part of the presidency due to the use of secret backroom deals, amplified those voices, who think it is time to reform the 30-year-old process.

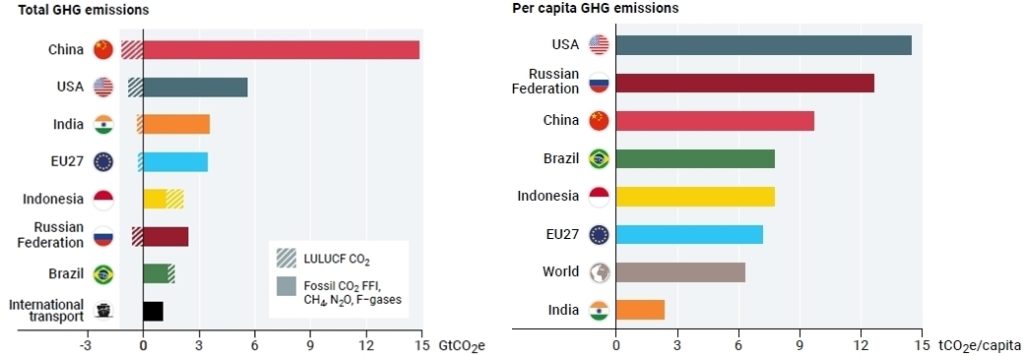

Some of the current challenges can be traced back to 1992 to the adoption of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, the UNFCCC. The Framework Convention contains several basic principles that have since become outdated, or at least we should interpret them differently today than in 1992. One of these principles is the principle of common but differentiated responsibility (CBDR), which refers to the common task of action against climate change for the countries of the world, but due to their different national opportunities and their different roles in causing climate change, they should participate differently in this task. This and the fact that the division of developed and developing country categories was made back in 1992, while the process does not take into account the changes that have taken place since then, leads to the fact that some countries can stay out of action against climate change, or the financing of action, while their levels of development and emissions could allow for more action, and even justify it.

Here, it is primarily worth thinking about, for example, the Gulf states, China, Brazil or Russia, which have since become the world’s strongest economies, members of the G20. Meanwhile they still have the status of a developing country under the UN climate convention, while their economic opportunities and emissions also exceed those of several European countries. Since most of the obligations in the UN climate change framework currently fall only on developed countries, it would definitely be worth changing this, because until these countries do their part properly in emission reduction efforts and, above all, in financing climate action, we will not be able to curb global climate change. By the way, this developed-developing division is not “set in stone”, since both Hungary and its region previously held an emerging economy status, but today they are considered a developed countries. But we can also think of the OECD organization, which brings together the world’s most developed countries, whose membership is constantly increasing, most recently, for example, Costa Rica joined. It is important to emphasize, however, that the purpose of the review of the 1992 situation is not for developed countries to shift the task of climate action to developing countries. A good example of this is the new fund set up to alleviate loss and damage, where, according to the plans, the funds will no longer be available to all developing countries, but only to the truly most vulnerable countries.

However, in order to take effective action against climate change, it is important that countries not only increase their commitments and level of ambition, but also implement them and monitor the results. It is important to see that even if current commitments were fully fulfilled, we would still not be able to meet the global warming target of 1.5°C, which is necessary to avoid the catastrophic consequences of climate change. As for whether the countries fulfill the nationally defined contributions made under the Paris Agreement, no one is currently holding the national governments accountable. Simon Stiell, the newly elected UNFCCC Executive Secretary, also dealt with this challenge. In his speech at the opening of COP27, he saw himself not only as an Executive Secretary, but also as “Accountability-Chief”, which was welcomed by both developed countries and non-governmental organizations. For this, the newly launched Enhanced Transparency Framework will provide the monitoring framework, however, for the time being, the Executive Secretary only has tools for exerting political pressure on governments that do not keep their commitments.

However, this does not necessarily have to remain the case either. In the past, there was already a procedure for dealing with such cases within the framework of the UNFCCC; the compliance mechanism operating under the Kyoto Protocol. Within this framework, the control and enforcement branches of the mechanism monitored the emission reduction activities of the countries in cooperation and initiated procedures in the event of non-compliance. Another example can be cited in the case of non-fulfillment of the National Energy and Climate Plans (NECP) of the EU member states. If a member state is unable to fulfill its commitments set in its NECT, it must report this in detail to the European Commission and take steps to meet the goals. Similar motivational mechanisms could be incorporated into the current framework, although similar initiatives have so far failed due to resistance from countries like China and the United States.

From the point of view of global climate policy processes, it may be worthwhile to reconsider the role of the UNFCCC Secretariat over time. Although it has been said several times by former executive secretaries that the Secretariat is not an implementing agency but a creator of international rules, with most of the detailed rules of the Paris Agreement having been adopted and the Kyoto Protocol soon to expire, it is questionable whether this should continue to be the case in the future. Along these lines, it would be important for the Secretariat to get closer to the actors who deliver climate action. Weaker steps have already been taken in this regard, such as the appointment of high-level climate champions from the business sector or the creation of the mitigation work program, in the framework of which they plan to specifically involve practitioners, companies, and local organizations in climate action. However, it would be important for the Secretariat to take on more direct support for the implementation of climate action measures as one of its main tasks in order to be able to call the action against climate change a success.

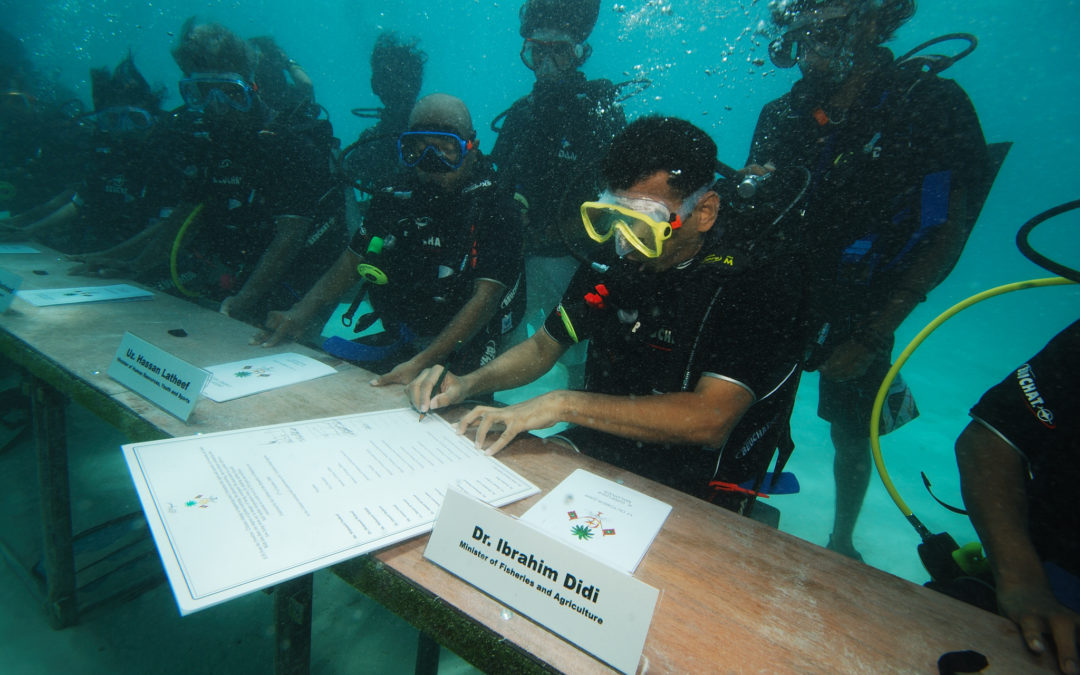

Finally, it is also worth thinking about how to measure the success of climate conferences. Of course, every year the international community and the host country holding the presidency of the COP would like to show some great results, however, if we consider that national strategy and legislative processes do not think in one-year cycles, it is difficult to see it as realistic that delegates arrive with new and more serious commitments every year to the conferences. In addition, we should not lose sight of the fact that the annual conferences with tens of thousands of people themselves have a serious carbon footprint, not to mention the transport needed to get there in the first place. These all send negative messages to the public. The public has great expectation of these events every year, which can cause a constant feeling of disappointment due to the above reasons. Of course, it is already an important result if every year the whole world focuses on climate change for at least two weeks, but it is possible that hosting a yearly such a large traveling circus is not justified. It may be sufficient to organize such large-scale events only every two years, and in the years between the COPs, it could be considered to hold only professional meetings without the participation of the full-scale “traveling circus”, i.e. exhibitions, art events and celebrities. Furthermore, it is also not incidental that the awarding of conference organization rights is beginning to resemble the procedure of football world cups; last year, Egypt was able to hold a conference without sufficient infrastructure, and this year, the United Arab Emirates, which is not exactly a climate champion, will host the world’s climate negotiators.

Of course, the above proposals are not intended to suggest that the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and its annual conferences are unnecessary and can be abandoned, however, in the process celebrating its 30th anniversary, the demands for the introduction of some serious reforms are increasingly felt in order to achieve the most important goal in the long term, to promote global action against climate change.