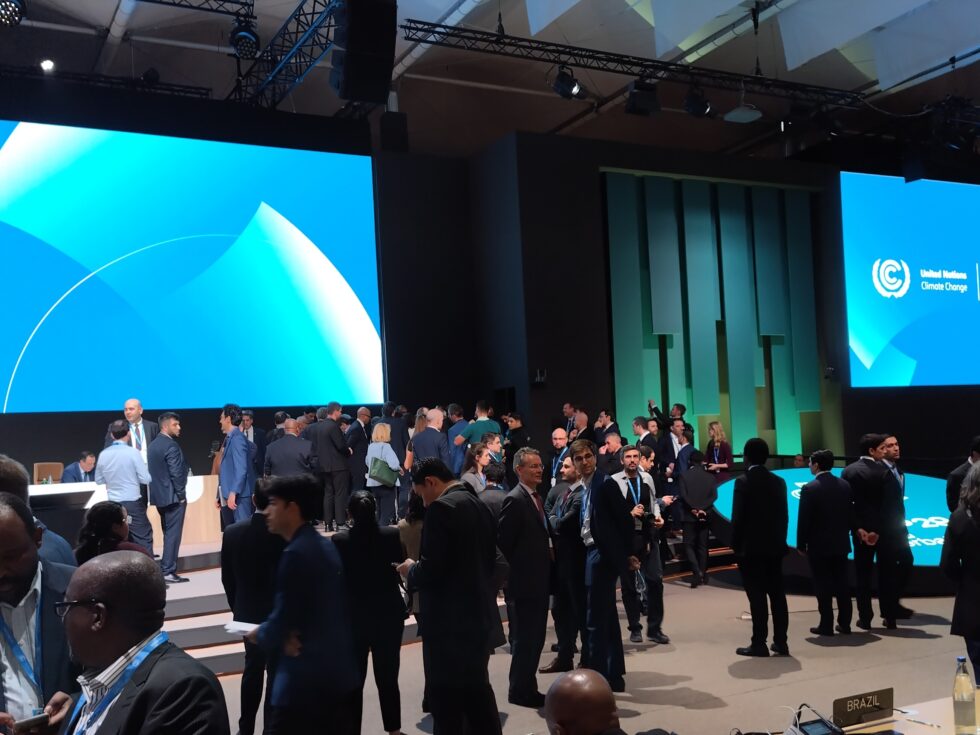

The latest annual UN climate conference recently concluded in Baku, where developing countries sought new financial resources, while developed nations aimed to secure strengthened emissions reduction measures. However, except for the Gulf countries, all parties left disappointed. What exactly happened in Azerbaijan, and what does it mean for the future?

Delegates from the world’s nations, alongside representatives from civil organizations and businesses, gathered for the 29th time to address the challenges of climate change. This year, the event took place in Baku’s Olympic Stadium. The various country groups arrived with differing expectations: developed countries wanted to establish stronger emissions reduction targets and programs to keep climate change under control, while developing nations sought increased funding for their activities. After more than two weeks of negotiations, decisions were finally adopted at dawn on Sunday, 36 hours behind schedule, leaving almost all sides dissatisfied.

High Expectations

The question of who should pay for the costs of the green transition and the damages caused by climate change has long been contentious. The 2015 Paris Agreement acknowledges the historical responsibility of developed nations for climate change, urging them to provide resources for the climate protection efforts of developing countries. Within this framework, the current climate finance goal, running until 2025, was established, with developed nations committing $100 billion annually to developing countries. As this goal approaches its end, negotiations over the past three years have focused on setting a new target for the period from 2025 to 2035.

Three main principles guided these talks: developed countries would continue to lead in providing resources, other economically capable nations would also contribute, and the annual funding target would rise above the current $100 billion.

Developing nations’ expectations varied widely. Some estimates suggest that achieving the national plans of developing countries through 2030 would require $5.1–6.8 trillion, or $455–584 billion annually, alongside an additional $215–387 billion annually for adaptation efforts. Meanwhile, developed nations face slowing economic growth, rising war and humanitarian expenses, and general fiscal constraints.

To address these expectations, developed countries proposed expanding the pool of contributors, including through greener financial flows from development banks and private sources, as well as involving nations that were classified as developing in 1992 but are now major emitters and economically strong, such as certain Asian countries and Gulf oil monarchies.

Developed nations also sought agreements on stronger emissions reduction measures, arguing that minimizing climate impacts would reduce future costs. A recent study suggests that every 1°C rise in temperature could shrink global GDP by 12%, making prevention a better investment.

Breakdown of Trust

Further complicating matters, this year’s conference was hosted by a resource-rich country with limited experience in international climate negotiations. Delays, poor organization, and communication issues hampered progress. The UNFCCC Secretariat tried to assist Azerbaijani diplomats, but the Secretariat is not designed to lead negotiations.

In the final days, public consultations ceased entirely, with Azerbaijan’s COP presidency holding closed-door meetings to secure agreements. The lack of competence and vision eroded trust, which collapsed completely when a negotiation document was mistakenly shared in an editable format, revealing that it had been drafted not by the Azerbaijani presidency but by Saudi Arabian representatives.

Saudi Arabia, leading a group of countries, aimed to block any agreements in Baku that would require ambitious new climate finance commitments or emissions reductions, as these would have implicated them in significant obligations. Their support for Azerbaijan’s presidency served their own interests.

Outcomes of the Talks

The Azerbaijani COP presidency sought to build trust by resolving long-standing negotiations on international carbon market mechanisms, which could mobilize $250 billion annually for emissions reduction measures. While launching international carbon trading is a significant achievement, other outcomes fell short.

The final decisions, adopted after a 36-hour delay, tripled the post-2025 climate finance goal to at least $300 billion annually from developed countries’ public funds, with efforts to raise the total to $1.3 trillion from all sources. However, this fell short of developing countries’ expectations. A proposal led by India to veto the decision was overruled by the Azerbaijani presidency.

Additionally, Gulf countries were not obligated to contribute to the new targets, leaving this as a voluntary option, despite China showing some openness to mandatory contributions. Meanwhile, the Mitigation Work Program aimed at stronger emissions reduction measures did not include new targets, while the decision on the UAE Dialogue was vetoed by developed nations, as it lacked sufficient commitments to limit global temperature rise and accelerate the energy transition.

Disappointment Across the Board

In summary, the Baku climate conference ended with all parties — except perhaps Saudi Arabia — leaving disappointed. Developing nations fell short of securing the resources they hoped for, while developed nations failed to achieve stronger emissions commitments. The limited outcomes of COP29, combined with geopolitical challenges, signal tough years ahead for international climate policy. It is essential that regions and nations pursue ambitious climate action domestically.